From Sportfishing

Fish Report for 2-7-2018

Diverted River Sustains California Wine Country, but It’s Killing Salmon

2-7-2018

Matt Wieser

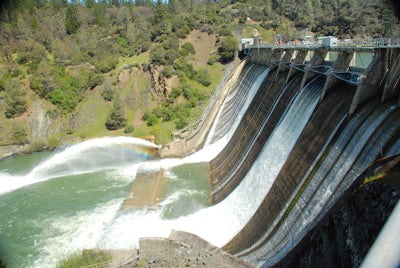

[Utility PG&E’s Potter Valley Project includes two dams on the Eel River that are up for relicensing. Water diversions into the Russian River for power generation are in jeopardy as salmon and steelhead remain at risk of extinction.]

FEW PEOPLE OUTSIDE Northern California have heard of the Eel River. But if you’re a wine lover, there’s a good chance you’ve enjoyed its water in the form of a golden chardonnay or a rich red merlot.

The Eel River was once home to one of the largest salmon populations on the West Coast. But for nearly a century, a large share of its flow has been diverted for hydroelectric power and irrigation, helping build Northern California into a world powerhouse of winemaking. Much of the wine produced in Mendocino and Sonoma counties would not exist without that diverted Eel River water.

So it should come as no surprise that the prospect of ending those water diversions is stirring concern across the region.

The water diversions are part of the Potter Valley Project, a 9.2-megawatt hydroelectric facility owned by utility Pacific Gas & Electric Co. (PG&E). It includes two dams on the Eel River and a hydroelectric powerhouse in the headwaters of the Russian River.

In a quirk of geography, the two rivers flow past each other only about a mile apart, separated by a ridge. A mile-long tunnel built through the ridge in 1908 diverts Eel River water into the Russian River, which then flows south into Mendocino and Sonoma counties. The Eel turns north and flows through Humboldt County.

The powerhouse was originally built to provide electricity for the town of Ukiah. For about 80 years, it’s been part of PG&E’s vast Northern California energy portfolio.

The Potter Valley Project is up for relicensing with the Federal Energy Regulatory Commission (FERC), a once-in-50-years process that is prompting a hard look at whether the dams still make sense.

A key issue is fish passage. Like so many hydroelectric facilities of its era, the Potter Valley Project was built with no regard for migratory fish. Scott Dam, the largest of the two dams, is a 130ft-high concrete monolith with no fish ladders to allow fish to get around the structure. It was built on the Eel River in 1922, forming Lake Pillsbury about 12 miles upstream from the diversion tunnel.

Scott Dam has cut off salmon and steelhead from more than 280 miles of habitat for nearly a century. Logging, erosion and other land disturbances, such as vineyard development, have contributed to habitat loss for the fish as well.

The Eel River once spawned as many as 1 million salmon annually, making it the third-largest producer among California rivers, after the Sacramento and Klamath, said Scott Greacen, conservation director of Friends of the Eel River. Today, salmon returning to spawn in the Eel number fewer than 1,000 fish.

Greacen’s group is campaigning to remove the Eel River dams. A key reason is that most of the habitat upstream of Scott Dam is on U.S. Forest Service land and remains relatively undisturbed. It still offers cool water temperatures that could serve as a refuge for salmon and steelhead as downstream temperatures warm amid climate change.

“One of the things we really, really treasure about the Eel is that our fish seem to be wild fish,” said Greacen. “There’s a real possibility of recovering them as wild fish and not depending on hatcheries. It could be the Eel is a fairly significant chunk of the wild fish left on the West Coast.”

The prospect of losing the dams is terrifying to farmers who depend on the Russian River. The diverted water has created a thriving agricultural economy. The Eel River, in reality, is the lifeblood for hundreds of wineries, artisanal fruit and vegetable growers, and livestock producers along the upper reaches of the Russian River.

In much of this region, the Russian would go dry in summer and fall without Eel River water. This is particularly true in Potter Valley itself, the farming region closest to the powerhouse, which has no viable groundwater available.

“The Potter Valley Project provides the only source of water we have,” said Janet Pauli, a board member of the Potter Valley Irrigation District. Pauli’s farm, a sixth-generation family operation, grows wine grapes, pears, hay and cattle – all thanks to diverted Eel River water.

“It changed the economy, it changed the crops we grow and the livestock we raise. It has been a boon,” Pauli said. “We are completely dependent on this water supply for our quality of life and for our economy. It is critically important.”

PG&E last year filed a formal notice with FERC that it intends to proceed with relicensing, a complicated process that takes at least five years. This triggered initial comments from other federal agencies that have a regulatory role.

One is the National Marine Fisheries Service, which hinted it may require PG&E to build some type of fish passage at Scott Dam. Similar requirements have been imposed on many dams up for relicensing over the past decade.

Fish passage could take many forms – from a basic concrete fish ladder to a new-fangled “salmon cannon,” which sucks fish through a tube and shoots them back out. Another option is a trap-and-haul program, in which fish are collected in tanker trucks and driven around the dam. All are expensive, raising the possibility that PG&E may not want to continue operating the dams.

Rep. Jared Huffman, D-San Rafael, recently convened regular meetings with the players to discuss the future of the Eel River dams. In a recent video posted by the group CalTrout, Huffman said PG&E has “indicated they no longer want to operate that as a hydroelectric project going forward.”

PG&E officials would not confirm that position. But David Moller, PG&E’s director of portfolio strategies in power generation, said decommissioning the dams is one of many options on the table. He emphasized the relicensing process is at a very early stage, and no decision has been made.

“We always are continually evaluating our power generation facilities as to their economics, how they fit in with our forecasted future power demands,” said Moller. “Certainly, potentially not continuing on with the project would be an option. But it’s certainly not the exclusive option.”

The economics of the Potter Valley Project are not what they once were. In 2007, PG&E was required by the National Marine Fisheries Service to divert less water through the tunnel and powerhouse to leave more water in the Eel River for migratory fish. This reduced power generation by around 50 percent.

It also slashed diversions to the Russian River from 160,000 acre-feet per year to around 77,000.

“That was a huge, huge change in the project,” Moller said. “It significantly reduced the power generation.”

This could shift the economics of the issue. Friends of the Eel River recently hired a consultant who found that just 5 acres of solar panels could generate more electricity than the Potter Valley Project now produces.

So it could work out that the water diverted for Russian River agriculture is the primary economic benefit of the Potter Valley Project. One solution, therefore, is to find a way to continue those diversions while also removing the dams.

An option is to raise Coyote Valley Dam to increase the capacity of Lake Mendocino, a 122,000 acre-foot reservoir on the Russian River about 5 miles downstream from Potter Valley, at the intersections of Highways 101 and 20. Owned by the United States Army Corps of Engineers, it was originally designed with a 36ft rise in mind. This would increase the water storage by about 75,000 acre-feet – roughly equaling today’s diversions from the Eel River.

The Potter Valley tunnel could remain in operation to divert excess winter flows into the Russian River, helping to fill that additional capacity at Lake Mendocino.

All that could satisfy demand downstream of Lake Mendocino, which includes the vast majority of the Russian River’s agricultural water users. But it would leave Potter Valley – the original beneficiaries of Eel River diversions – high and dry in the summer.

The Potter Valley Irrigation District has studied the idea of building its own new reservoir somewhere in the surrounding watershed, Pauli said. Several possibilities were investigated, but none was big enough to make economic sense.

Still, Pauli is optimistic that some compromise can be reached to protect both the water supply and the fisheries.

With a PhD in zoology, Pauli also has a deep concern for the salmon, steelhead and other wildlife in the two rivers. She notes, for instance, that the Russian River is home to western pond turtles and foothill yellow-legged frogs. Both are endangered species that depend, to some degree, on the same Eel River water diversions that built Potter Valley’s farm economy.

“We will have to be very, very wise about how we protect this shared resource,” Pauli said. “We’re on a ride, and nobody knows exactly what the destination is.”

Matt Weiser is a contributing editor at Water Deeply. Contact him at matt@newsdeeply.org or via Twitter at @matt_weiser.

Photos

< Previous Report Next Report >

More Reports

12-18-2017California’s drought may have officially been declared over in the spring, but the effects of the five-year drought are still taking a toll on the state’s forests, new information shows. Last November, the number of trees that died in California forests since 2010 was estimated by the U.S. Forest Service at 102 million, with 62 million dying in 2016 alone. The latest aerial survey shows that tree mortality is continuing, although not with the same intensity. The Forest Service reported 27 million trees died in the last year,...... Read More

5-22-2017

Climate change is the single biggest threat to native salmonids in California, according to a new study from California Trout...... Read More

Website Hosting and Design provided by TECK.net